| Family Non-Fiction posted September 25, 2009 |

|

Hug them, squeeze them, love them . . . every day.

Top of the Mountain

by Mastery

Testimony! Contest Winner

Determining the one thing that affected my life the most is not a problem. I could just cry and moan about the nine foster homes I lived in from the time I was five until I turned seventeen, but I just never considered any of that life-changing.

Or, the eight years I spent on active duty as a U.S. Marine. That will change you a tad. Whining about how tough boot camp was, the discipline. All of that built character and made me a man in spite of myself.

I could complain that none of my immediate family was known to me except for one sister in Florida, or that my wife had no living relatives at all.

True, our lives are molded by multitudes of events -- both good and bad. We try to remember the good things and purposely shove the unpleasant ones out of our minds. Those that we attempt to dismiss, however, are the happenings we will never forget.

I would probably be wise to say my life changed when I married my current wife who is the love of my life. But, one thing above all others made me the man I am today because it changed my outlook on life.

One of the most joyful events for all of us is the birth of our children. Especially our first child. And in the case of the father -- a son is extra special.

On February 21, 1967, our son, Robert Charles Hartson III was born at 9:05 A.M. in Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Illinois. Remember, in those days we didn't know if it was going to be a boy or a girl and Daddy was not allowed anywhere near the birthing room, so we learned the stress-relieving art of pacing the hall and smoking cigarettes in anticipation of news from the doctor.

It was as if heaven played my song that morning when the doctor came out and said, "Congratulations, Mr. Hartson, you have a son."

All was not good however, because we were later informed that due to certain "female problems", my wife would not be allowed a second pregnancy. Further, adoption laws were more strict in those days so we decided not to consider that option.

__________*******__________

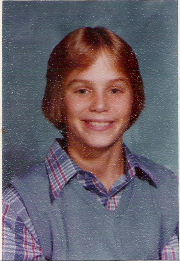

Fourteen years flew by, and Bobby was an excellent student in school. He loved little league baseball, the Detroit Tigers, Lions football, bowling and music. He played trumpet in the middle school band and loved Bob Seger, Journey and The Doobie Brothers.

A bit spoiled, perhaps, being our only child, he was still very well-liked and an extremely popular kid with his classmates.

On the Saturday morning after Thanksgiving day in 1981, I drove Bobby and four kids on his bowling team to the bowling alley for their Saturday morning league. The parents took turns transporting them and it was my turn.

Two hours later, I was taking a break from mowing the lawn when the phone rang. It was Bobby.

"Dad, you don't have to come and get me if you don't want to. I can ride home with Paul and the rest of the kids. Okay?"

It didn't occur to me to ask if Paul's father would be the one bringing them home. "I guess it's alright, son. Here, ask your Mom if it's okay."

I started to hand the phone to his mother, when Bobby continued.

"And, uuh, Dad . . . somebody stole my bowling bag. It's gone."

"What? That bag's brand new, son. How could that be? Where did you leave it?"

"I know, dad -- I'm sorry. I put it under our table. I was bowling and when we were done I went to put it in the bag, but it was gone."

I handed off the phone, a bit agitated.

I heard Pat warn him to come right home. "No Lolly-gagging." Why did I give the phone over to my wife? I don't know. Why do we do the things we do? Was I mad about the new bag being stolen? I suppose. Anyway, Pat hung up and went about finishing her ironing and I went back to mowing the lawn.

Forty minutes later, the phone rang again; it was Harper Grace Hospital's emergency room.

**************

When we got to the hospital in downtown Detroit, an hour and forty-five minutes had passed since the accident, but we were allowed to see Bobby.

He was unconscious, lying under sterile white sheets. It was the only bed in the room. I remember thinking he looked so hurt and all alone and I started to blame myself.

A respirator was hooked up to help him breathe. A respirator? His eyes were closed and a small amount of blood trickled from the corners of his eyes. The skin around his eyes was black like a raccoon's. His head was bandaged and appeared to be swollen to twice its normal size.

I felt sick to my stomach and Pat hadn't stopped screaming and crying since the hospital had called. Seeing Bobby lying there, she wailed. I could not calm her. Hell, I could barely calm myself. On the phone we had been told that Bobby suffered a skull fracture. They said it was fairly common and he would be okay.

A nurse came in to talk with us. "Do you folks know a boy named Paul?"

"Yes," I said, "He's Bobby's best friend."

"On your son's bowling team, is that right, sir?"

"Yes. He would have been with the rest of them. He was, wasn't he?"

"Yes, sir. He told us what happened, I thought you'd want to know. None of the other children were seriously injured. They were all riding home with a boy named Tim Jeffries." Her voice dropped. "He only had his driver's license for three weeks. He was showing off a bit, driving down a shortcut, Collins Road over in Farmington Hills. It's very muddy this time of year. Anyway, the boy went out of control and hit a tree. But your son was carrying his bowling ball in his lap instead of putting it in the trunk with the others. Something about a lost bowling bag?" She paused as Pat and I looked at one another.

"Yes, then what?" I said.

"Well, when this Tim hit the tree, the impact caused the ball to fly back up and hit Bobby in the head. I'm so sorry."

"Look at my baby!" Pat screamed. "Oh, my god, Bob. He looks terrible! What's going to happen? Will he be alright? Ahhhhhhhhh!" She pounded her fists on my chest, completely out of control. I barely felt it. I knew I had to stay strong and yet, I didn't know how I could.

I told Pat things would be okay, but I knew I was lying. I wasn't sure of anything. Nobody seemed to be. I suspected the worst, even though some nurses tried to assure me otherwise.

An intern took us to the side an hour later. "We've been waiting for the swelling to come down. Your son will be alright. He's suffered a skull fracture but they are going to operate right away in order to relieve some of that pressure. Doctor Edelman is with the University Of Michigan medical staff. He's considered the best neurosurgeon in Michigan. He will be performing the procedure. He's a fine doctor-- your son will be okay." He patted us on the shoulders.

I didn't let on to Pat, but I didn't believe him. I couldn't. The way my boy looked, the bleeding . . . the entire situation was like being in the middle of a horrible nightmare . . . one where waking up was not an option, or if you woke up you would face the worst. And, the tragedy was still unfolding.

Staying next door at Ronald McDonald House, we tried to sleep and waited for anything positive, but three long days later doctors took us into a private room. They slowly pulled the blinds. Closed the doors. They told us there was no hope. No brain wave. Our fourteen-year-old son was brain-dead.

***************

They came to see him, to offer their love and respect. The December sun was shining that second day of December 1981.

Seven inches of snow covered the ground like a mandatory white blanket. At the graveside, dads were wearing dark suits and ties. Teary-eyed moms had their arms wide open. There were no painted flower dresses wrapped around any of them.

Bobby's teen pals wore jeans, long-sleeved shirts, and December jackets. The girls hardly looked like their fourteen and fifteen years; they wore black high heels and makeup and clutched tiny purses.

Pat and I sat in the front row, leaning upon one another like wilted flowers. Her head tilted to the side, lying on my shoulder, my arm was wrapped around her trembling shoulders.

After the service at the cemetery, Bobby was left alone; his casket sitting like a polished, unearthed artifact suspended above the freshly dug hole in the ground as people drifted away.

The men offered their strong hands and hearty hugs. The women comforted my wife and shared cheek to cheek whispers and perfume-laden embraces.

The faces of our son's friends were sad; they were somber, unbelieving faces. They told each other stories of disorientation and disbelief. In their eyes, destroyed faith begged for answers:

"Just last week I had music class with him and we. . . ."

"Bobby was in my math, fourth hour, with Hutchinson and he . . ."

"I've still got his 'Journey' CD in my locker, too. What should I do with it now?"

So many questions . . . so few answers. A reason? Please? Some relief for the hurt. "Please, God, help us," I begged. "God in heaven, please!" I held a trembling, sobbing Pat in my arms. My own tears wetting her forehead.

Then, something unexpected happened as we were leaving Memorial gardens. Father Drew Harding approached Pat and me and hugged us. Pat could not contain her tears, nor could I, but we thanked him for the service.

It was then that we learned something that would stay with us to forever. It is the one constant that we have been able to rely on:

Father Harding said, "You know, Bob -- there is one positive, and only one that will come out of this for both of you."

"What? What are you saying, Father? How can anything be positive when we just buried our son? What is it, please?"

He looked into our eyes, alternating from one of us to the other. "You will never suffer like this again. You see, you folks have been to the top of the mountain. There is nothing -- absolutely nothing worse than losing a child--an only child at that. When I say you have been to the top of the mountain, I am saying that nothing in your life will ever hurt as much as burying Bobby. You will be able to handle anything that comes your way for the rest of your life. You may not understand this now, but someday you will . . . believe me. I'm sorry folks. God bless you."

**************

My wife and I rode home in silence. I drove.

I'll never forget the incredible hush we found in his room. We closed the door and it stayed closed for nearly six months.

We cried and wailed in tormented agony, for days and weeks after disappearing behind the walls of our house that was once called a home.

The phone rang, again and again. Condolences. Days passed, and the phone stopped ringing.

My job called after a week or so. I didn't answer.

After a while, sympathy cards stopped filling the mailbox, and newspapers piled up on the front porch.

We had gone out as a family to buy a tree that year. It wasn't decorated yet and was leaning in the corner of the family room when we got home from the funeral. There was no Christmas that year.

Determining the one thing that affected my life the most is not a problem. I could just cry and moan about the nine foster homes I lived in from the time I was five until I turned seventeen, but I just never considered any of that life-changing.

Or, the eight years I spent on active duty as a U.S. Marine. That will change you a tad. Whining about how tough boot camp was, the discipline. All of that built character and made me a man in spite of myself.

I could complain that none of my immediate family was known to me except for one sister in Florida, or that my wife had no living relatives at all.

True, our lives are molded by multitudes of events -- both good and bad. We try to remember the good things and purposely shove the unpleasant ones out of our minds. Those that we attempt to dismiss, however, are the happenings we will never forget.

I would probably be wise to say my life changed when I married my current wife who is the love of my life. But, one thing above all others made me the man I am today because it changed my outlook on life.

One of the most joyful events for all of us is the birth of our children. Especially our first child. And in the case of the father -- a son is extra special.

On February 21, 1967, our son, Robert Charles Hartson III was born at 9:05 A.M. in Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Illinois. Remember, in those days we didn't know if it was going to be a boy or a girl and Daddy was not allowed anywhere near the birthing room, so we learned the stress-relieving art of pacing the hall and smoking cigarettes in anticipation of news from the doctor.

It was as if heaven played my song that morning when the doctor came out and said, "Congratulations, Mr. Hartson, you have a son."

All was not good however, because we were later informed that due to certain "female problems", my wife would not be allowed a second pregnancy. Further, adoption laws were more strict in those days so we decided not to consider that option.

__________*******__________

Fourteen years flew by, and Bobby was an excellent student in school. He loved little league baseball, the Detroit Tigers, Lions football, bowling and music. He played trumpet in the middle school band and loved Bob Seger, Journey and The Doobie Brothers.

A bit spoiled, perhaps, being our only child, he was still very well-liked and an extremely popular kid with his classmates.

On the Saturday morning after Thanksgiving day in 1981, I drove Bobby and four kids on his bowling team to the bowling alley for their Saturday morning league. The parents took turns transporting them and it was my turn.

Two hours later, I was taking a break from mowing the lawn when the phone rang. It was Bobby.

"Dad, you don't have to come and get me if you don't want to. I can ride home with Paul and the rest of the kids. Okay?"

It didn't occur to me to ask if Paul's father would be the one bringing them home. "I guess it's alright, son. Here, ask your Mom if it's okay."

I started to hand the phone to his mother, when Bobby continued.

"And, uuh, Dad . . . somebody stole my bowling bag. It's gone."

"What? That bag's brand new, son. How could that be? Where did you leave it?"

"I know, dad -- I'm sorry. I put it under our table. I was bowling and when we were done I went to put it in the bag, but it was gone."

I handed off the phone, a bit agitated.

I heard Pat warn him to come right home. "No Lolly-gagging." Why did I give the phone over to my wife? I don't know. Why do we do the things we do? Was I mad about the new bag being stolen? I suppose. Anyway, Pat hung up and went about finishing her ironing and I went back to mowing the lawn.

Forty minutes later, the phone rang again; it was Harper Grace Hospital's emergency room.

**************

When we got to the hospital in downtown Detroit, an hour and forty-five minutes had passed since the accident, but we were allowed to see Bobby.

He was unconscious, lying under sterile white sheets. It was the only bed in the room. I remember thinking he looked so hurt and all alone and I started to blame myself.

A respirator was hooked up to help him breathe. A respirator? His eyes were closed and a small amount of blood trickled from the corners of his eyes. The skin around his eyes was black like a raccoon's. His head was bandaged and appeared to be swollen to twice its normal size.

I felt sick to my stomach and Pat hadn't stopped screaming and crying since the hospital had called. Seeing Bobby lying there, she wailed. I could not calm her. Hell, I could barely calm myself. On the phone we had been told that Bobby suffered a skull fracture. They said it was fairly common and he would be okay.

A nurse came in to talk with us. "Do you folks know a boy named Paul?"

"Yes," I said, "He's Bobby's best friend."

"On your son's bowling team, is that right, sir?"

"Yes. He would have been with the rest of them. He was, wasn't he?"

"Yes, sir. He told us what happened, I thought you'd want to know. None of the other children were seriously injured. They were all riding home with a boy named Tim Jeffries." Her voice dropped. "He only had his driver's license for three weeks. He was showing off a bit, driving down a shortcut, Collins Road over in Farmington Hills. It's very muddy this time of year. Anyway, the boy went out of control and hit a tree. But your son was carrying his bowling ball in his lap instead of putting it in the trunk with the others. Something about a lost bowling bag?" She paused as Pat and I looked at one another.

"Yes, then what?" I said.

"Well, when this Tim hit the tree, the impact caused the ball to fly back up and hit Bobby in the head. I'm so sorry."

"Look at my baby!" Pat screamed. "Oh, my god, Bob. He looks terrible! What's going to happen? Will he be alright? Ahhhhhhhhh!" She pounded her fists on my chest, completely out of control. I barely felt it. I knew I had to stay strong and yet, I didn't know how I could.

I told Pat things would be okay, but I knew I was lying. I wasn't sure of anything. Nobody seemed to be. I suspected the worst, even though some nurses tried to assure me otherwise.

An intern took us to the side an hour later. "We've been waiting for the swelling to come down. Your son will be alright. He's suffered a skull fracture but they are going to operate right away in order to relieve some of that pressure. Doctor Edelman is with the University Of Michigan medical staff. He's considered the best neurosurgeon in Michigan. He will be performing the procedure. He's a fine doctor-- your son will be okay." He patted us on the shoulders.

I didn't let on to Pat, but I didn't believe him. I couldn't. The way my boy looked, the bleeding . . . the entire situation was like being in the middle of a horrible nightmare . . . one where waking up was not an option, or if you woke up you would face the worst. And, the tragedy was still unfolding.

Staying next door at Ronald McDonald House, we tried to sleep and waited for anything positive, but three long days later doctors took us into a private room. They slowly pulled the blinds. Closed the doors. They told us there was no hope. No brain wave. Our fourteen-year-old son was brain-dead.

***************

They came to see him, to offer their love and respect. The December sun was shining that second day of December 1981.

Seven inches of snow covered the ground like a mandatory white blanket. At the graveside, dads were wearing dark suits and ties. Teary-eyed moms had their arms wide open. There were no painted flower dresses wrapped around any of them.

Bobby's teen pals wore jeans, long-sleeved shirts, and December jackets. The girls hardly looked like their fourteen and fifteen years; they wore black high heels and makeup and clutched tiny purses.

Pat and I sat in the front row, leaning upon one another like wilted flowers. Her head tilted to the side, lying on my shoulder, my arm was wrapped around her trembling shoulders.

After the service at the cemetery, Bobby was left alone; his casket sitting like a polished, unearthed artifact suspended above the freshly dug hole in the ground as people drifted away.

The men offered their strong hands and hearty hugs. The women comforted my wife and shared cheek to cheek whispers and perfume-laden embraces.

The faces of our son's friends were sad; they were somber, unbelieving faces. They told each other stories of disorientation and disbelief. In their eyes, destroyed faith begged for answers:

"Just last week I had music class with him and we. . . ."

"Bobby was in my math, fourth hour, with Hutchinson and he . . ."

"I've still got his 'Journey' CD in my locker, too. What should I do with it now?"

So many questions . . . so few answers. A reason? Please? Some relief for the hurt. "Please, God, help us," I begged. "God in heaven, please!" I held a trembling, sobbing Pat in my arms. My own tears wetting her forehead.

Then, something unexpected happened as we were leaving Memorial gardens. Father Drew Harding approached Pat and me and hugged us. Pat could not contain her tears, nor could I, but we thanked him for the service.

It was then that we learned something that would stay with us to forever. It is the one constant that we have been able to rely on:

Father Harding said, "You know, Bob -- there is one positive, and only one that will come out of this for both of you."

"What? What are you saying, Father? How can anything be positive when we just buried our son? What is it, please?"

He looked into our eyes, alternating from one of us to the other. "You will never suffer like this again. You see, you folks have been to the top of the mountain. There is nothing -- absolutely nothing worse than losing a child--an only child at that. When I say you have been to the top of the mountain, I am saying that nothing in your life will ever hurt as much as burying Bobby. You will be able to handle anything that comes your way for the rest of your life. You may not understand this now, but someday you will . . . believe me. I'm sorry folks. God bless you."

**************

My wife and I rode home in silence. I drove.

I'll never forget the incredible hush we found in his room. We closed the door and it stayed closed for nearly six months.

We cried and wailed in tormented agony, for days and weeks after disappearing behind the walls of our house that was once called a home.

The phone rang, again and again. Condolences. Days passed, and the phone stopped ringing.

My job called after a week or so. I didn't answer.

After a while, sympathy cards stopped filling the mailbox, and newspapers piled up on the front porch.

We had gone out as a family to buy a tree that year. It wasn't decorated yet and was leaning in the corner of the family room when we got home from the funeral. There was no Christmas that year.

Testimony! Contest Winner |

Recognized |

The picture is of Bobby . . . a school picture taken one month before the accident.

It happened in 1981 but I feel it most acutely at the time of his birthday which was the 21st of February. 1967. Although

Christmas is another bad one for us as you can imagine. Thank you for reading. Bob

Pays

one point

and 2 member cents. It happened in 1981 but I feel it most acutely at the time of his birthday which was the 21st of February. 1967. Although

Christmas is another bad one for us as you can imagine. Thank you for reading. Bob

You need to login or register to write reviews. It's quick! We only ask four questions to new members.

© Copyright 2024. Mastery All rights reserved.

Mastery has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work.