| Biographical Non-Fiction posted January 28, 2024 | Chapters: |

...5 6 -7- 8...

|

|

Looking for ...

A chapter in the book Jonathan's Story

The Person Within

by Wendy G

Jonathan’s wheelchair was supportive and comfortable, but he still needed to be repositioned frequently. We had a beanbag, and we bought him a comfortable armchair contoured so he could not fall out. We made him comfortable on the floor or the beanbag to relax and loosen his limbs with gentle stretches to alleviate the stiffness from always being in a sitting position.

He seemed to be biting his arm much less – that was our guide to pain and discomfort – and we were more in tune with the sources of his distress. We sensed that he was starting to notice more and take more interest in his activities and environment.

**********

We worked with him to try to achieve some success at sitting unaided, surrounding him with cushions and with the beanbag behind him.

Children first learn to sit cross-legged, and that’s how we started.

Initially, he would sway to either side or fall forward if he was unsupported; we could not let go of him. But gradually, over many months, with better head control, and improved posture, we had some success. He learned to sit cross-legged on the floor and maintain his balance! Only for a few minutes, but he had some independence, and it was good for his legs and muscle tone.

This normal milestone is important for babies, and a source of pleasure to their parents, but when it takes ten years to achieve this skill, the joy is multiplied. He lost the skill when his tendons tightened over the next couple of years. Too short a time for being like everyone else, but at least he experienced that success for a while!

Anna, Bella, and Joe would give him a choice of age-appropriate toys to reach for and hold – we also wanted to keep his arms moving and maximise the use of his hands, with being able to grasp and release at will. Gentle stretching – his contractures made such things painful, but these things were important.

**********

Jonathan always loved music, and his tastes were many and varied, from classical through to rock, pop, and country, but he also enjoyed African music with strong drumbeats and the music of our first nations people groups, particularly with didgeridoos.

We played a variety of genres for him to enjoy.

If it was lively music, he would jig in his wheelchair, his face alive and happy as he danced along. If the music were sad, he would listen attentively … and then tears would slowly and gently roll down his cheeks. He entered emotionally into whatever mood the composer wanted to convey – every time. He experienced music, deep in his soul, at a level that many “normal” people have never experienced or understood.

Our three children had piano lessons, and Jonathan would sit in his wheelchair beside each during their daily practice. For each one, he would listen intently as they played, face raised. If they struck a wrong note, he would moan and look sad. If they did it on purpose, he could tell – and he would laugh. He understood the joke. Humour is a sign of a functional brain. More importantly, he understood the music, and he sensed what was right and what was not.

However, for each of his siblings, there was always one song they had to practise which he disliked, a different song for each one. He would get very distressed, to the point he would have to be taken to the other end of the house.

“But Jonathan,” they would exclaim, “I must practise that one! I have a music exam coming up!” He never made a mistake or became confused about which piece he disliked for each one. It became the family joke. “Quick, take him to his room. I’m about to practise the one he hates!”

There were also times they would seat him on the piano stool and help him play the keys. The sense of wonder on his face was beautiful to see. One of the children would hold him, while another helped him play. Then they would wedge him between them and let him play on his own.

And then one day, he sat alone at the piano, on the stool by himself, with a child hovering on each side, arms ready to support him if he lost his balance, and he “played” the piano by himself. Just the pleasure of striking the notes, without help. It didn’t make music as such, but it was an amazing achievement for a child who had been written off. One of my favourite photos is of Jonathan sitting “playing” the piano. An extraordinary accomplishment. For most people, no, but for him, yes.

**********

If he heard a piece of music or a song on the car radio, he knew whether he liked it or not – and never forgot the ones he liked. We were returning from the children’s hospital after a late afternoon appointment one day, and he was tired and hungry. He started to cry. Then a song came on the car radio which I am positive he had not heard for many months. He remembered it. The crying ceased immediately, and he was relaxed and happy again. Such is the power of music to cheer and encourage.

And this was another insight into his closed world. His memory was excellent in some areas, and music was one of them.

**********

Spatial awareness was another surprising skill. When we moved into our new home, he was the first of the four to recognise the routes for getting home. The others were quite unsure of the nearby streets and access routes for a while after our move - but not Jonathan.We could approach the house from any of the four directions and he always knew when we were getting close. How did we know he knew?

We could tell, because he loved travelling in the car, and did not like having to get out of the car when we arrived at our destination. We would always have to let him know ahead of time. “Home in five minutes!” or “We’re nearly there!” Regardless, he would always get distressed as we neared our home and then cry for the first few minutes after the car stopped. Another family joke - who will take him for a quick walk and give him some distraction for a few minutes, so he could accept that the car-ride has stopped?

Similarly, whenever he had to get out of the car, any where, any time, it was the same - school, shops, outings .... The only time he happily accepted finishing a car ride was when we drove over two days to an interstate destination, about six hundred kilometres each day. That was, according to Jonathan, a "proper" car ride! But he didn't complain about getting out of the car.

Marco, his birth father, came on occasions to take his son for a weekend to spend some time with his grandparents. Marco lived more than an hour’s drive from us. One time, Marco was bringing Jonathan back to us and exited from the motorway. He then needed to do a right-hand turn, followed by a left into our street. He missed the turn into our street.

Jonathan became very distressed, vocalising about the need to turn around. Sounds, not words. He remained agitated until Marco corrected his route and turned into our street. How does a child who is perceived to be severely mentally disabled and who is legally blind manage to know such things? He had the senses of a homing pigeon, and he never made a mistake. It was uncanny.

*********

The longer we had Jonathan the more we saw that he had his own form of intelligence. How arrogant people sometimes are to disrespect disabled people, and denigrate them and their different abilities, which may not show up on an intelligence test, but which will be recognised if one looks for them with discernment.

Above all, they are people with feelings, human beings who merit the same care and love as others. We are all on a spectrum of abilities, and there is no point at which we can dismiss a person as useless, unworthy, or without value. Such judgment is not ours to offer.

How many times did I advocate for Jonathan even with specialists who should have known better? To some, in fact, distressingly, to the majority, people like Jonathan were just cases, to be hurried through and rapidly dismissed. How many really had the patience or desire to “find a way” for Jonathan’s life to be meaningful and happy?

I tried to put myself in Jonathan’s place. Sometimes I just rested my hand on his beating heart – and I knew we had done the right thing in fostering him. Such moments made up for all the hard times, and were a source of strength for keeping me going later on.

He was and is a blessing to our family.

He will go through life without ever uttering a single word. I have never heard him say “I love you!” and I never will, but I know he loves me.

Story of the Month contest entry

Jonathan’s wheelchair was supportive and comfortable, but he still needed to be repositioned frequently. We had a beanbag, and we bought him a comfortable armchair contoured so he could not fall out. We made him comfortable on the floor or the beanbag to relax and loosen his limbs with gentle stretches to alleviate the stiffness from always being in a sitting position.

He seemed to be biting his arm much less – that was our guide to pain and discomfort – and we were more in tune with the sources of his distress. We sensed that he was starting to notice more and take more interest in his activities and environment.

**********

We worked with him to try to achieve some success at sitting unaided, surrounding him with cushions and with the beanbag behind him.

Children first learn to sit cross-legged, and that’s how we started.

Initially, he would sway to either side or fall forward if he was unsupported; we could not let go of him. But gradually, over many months, with better head control, and improved posture, we had some success. He learned to sit cross-legged on the floor and maintain his balance! Only for a few minutes, but he had some independence, and it was good for his legs and muscle tone.

This normal milestone is important for babies, and a source of pleasure to their parents, but when it takes ten years to achieve this skill, the joy is multiplied. He lost the skill when his tendons tightened over the next couple of years. Too short a time for being like everyone else, but at least he experienced that success for a while!

Anna, Bella, and Joe would give him a choice of age-appropriate toys to reach for and hold – we also wanted to keep his arms moving and maximise the use of his hands, with being able to grasp and release at will. Gentle stretching – his contractures made such things painful, but these things were important.

**********

Jonathan always loved music, and his tastes were many and varied, from classical through to rock, pop, and country, but he also enjoyed African music with strong drumbeats and the music of our first nations people groups, particularly with didgeridoos.

We played a variety of genres for him to enjoy.

If it was lively music, he would jig in his wheelchair, his face alive and happy as he danced along. If the music were sad, he would listen attentively … and then tears would slowly and gently roll down his cheeks. He entered emotionally into whatever mood the composer wanted to convey – every time. He experienced music, deep in his soul, at a level that many “normal” people have never experienced or understood.

Our three children had piano lessons, and Jonathan would sit in his wheelchair beside each during their daily practice. For each one, he would listen intently as they played, face raised. If they struck a wrong note, he would moan and look sad. If they did it on purpose, he could tell – and he would laugh. He understood the joke. Humour is a sign of a functional brain. More importantly, he understood the music, and he sensed what was right and what was not.

However, for each of his siblings, there was always one song they had to practise which he disliked, a different song for each one. He would get very distressed, to the point he would have to be taken to the other end of the house.

“But Jonathan,” they would exclaim, “I must practise that one! I have a music exam coming up!” He never made a mistake or became confused about which piece he disliked for each one. It became the family joke. “Quick, take him to his room. I’m about to practise the one he hates!”

There were also times they would seat him on the piano stool and help him play the keys. The sense of wonder on his face was beautiful to see. One of the children would hold him, while another helped him play. Then they would wedge him between them and let him play on his own.

And then one day, he sat alone at the piano, on the stool by himself, with a child hovering on each side, arms ready to support him if he lost his balance, and he “played” the piano by himself. Just the pleasure of striking the notes, without help. It didn’t make music as such, but it was an amazing achievement for a child who had been written off. One of my favourite photos is of Jonathan sitting “playing” the piano. An extraordinary accomplishment. For most people, no, but for him, yes.

**********

If he heard a piece of music or a song on the car radio, he knew whether he liked it or not – and never forgot the ones he liked. We were returning from the children’s hospital after a late afternoon appointment one day, and he was tired and hungry. He started to cry. Then a song came on the car radio which I am positive he had not heard for many months. He remembered it. The crying ceased immediately, and he was relaxed and happy again. Such is the power of music to cheer and encourage.

And this was another insight into his closed world. His memory was excellent in some areas, and music was one of them.

**********

Spatial awareness was another surprising skill. When we moved into our new home, he was the first of the four to recognise the routes for getting home. The others were quite unsure of the nearby streets and access routes for a while after our move - but not Jonathan.We could approach the house from any of the four directions and he always knew when we were getting close. How did we know he knew?

We could tell, because he loved travelling in the car, and did not like having to get out of the car when we arrived at our destination. We would always have to let him know ahead of time. “Home in five minutes!” or “We’re nearly there!” Regardless, he would always get distressed as we neared our home and then cry for the first few minutes after the car stopped. Another family joke - who will take him for a quick walk and give him some distraction for a few minutes, so he could accept that the car-ride has stopped?

Similarly, whenever he had to get out of the car, any where, any time, it was the same - school, shops, outings .... The only time he happily accepted finishing a car ride was when we drove over two days to an interstate destination, about six hundred kilometres each day. That was, according to Jonathan, a "proper" car ride! But he didn't complain about getting out of the car.

Marco, his birth father, came on occasions to take his son for a weekend to spend some time with his grandparents. Marco lived more than an hour’s drive from us. One time, Marco was bringing Jonathan back to us and exited from the motorway. He then needed to do a right-hand turn, followed by a left into our street. He missed the turn into our street.

Jonathan became very distressed, vocalising about the need to turn around. Sounds, not words. He remained agitated until Marco corrected his route and turned into our street. How does a child who is perceived to be severely mentally disabled and who is legally blind manage to know such things? He had the senses of a homing pigeon, and he never made a mistake. It was uncanny.

*********

The longer we had Jonathan the more we saw that he had his own form of intelligence. How arrogant people sometimes are to disrespect disabled people, and denigrate them and their different abilities, which may not show up on an intelligence test, but which will be recognised if one looks for them with discernment.

Above all, they are people with feelings, human beings who merit the same care and love as others. We are all on a spectrum of abilities, and there is no point at which we can dismiss a person as useless, unworthy, or without value. Such judgment is not ours to offer.

How many times did I advocate for Jonathan even with specialists who should have known better? To some, in fact, distressingly, to the majority, people like Jonathan were just cases, to be hurried through and rapidly dismissed. How many really had the patience or desire to “find a way” for Jonathan’s life to be meaningful and happy?

I tried to put myself in Jonathan’s place. Sometimes I just rested my hand on his beating heart – and I knew we had done the right thing in fostering him. Such moments made up for all the hard times, and were a source of strength for keeping me going later on.

He was and is a blessing to our family.

He will go through life without ever uttering a single word. I have never heard him say “I love you!” and I never will, but I know he loves me.

Recognized |

Earned A Seal Of Quality |

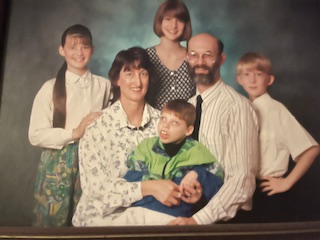

Anna was about thirteen, and Joe (on the right) was nearly nine.

© Copyright 2024. Wendy G All rights reserved.

Wendy G has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work.