At Home in Mississippi : John Seay's Head by BethShelby |

Death was not something I handled well as a child. The first time I saw a dead animal, I was horrified. We lived on a farm and animals were killed for food, especially chickens and hogs. I refused to touch meat, and I hated watching other people eat meat.

My aversion to death was so bad, Mother had to screen the Mother Goose stories she read to me. I cried when Jack killed the giant. I thought 'The Three Little Pigs' and 'Billy Goat Gruff' were gruesome stories. When Mother took me to the theater to watch Bambi, I loved it until Bambi's mother died. She took me from the theater convulsed in tears.

I don't think kids today obsess about these things. I was living in the pre-television days. My world was fairly sheltered except for a radio, which only picked up two static-filled stations. My only other exposure to life's unpleasant aspects came from conversations I overheard from the adults. Now, children watch people being gunned down before they get out of diapers, and they think nothing of mastering the art of shooting the characters on their game sets before entering kindergarten. I don't think my own children were anywhere nearly as sensitive as I was. Mother was worried. She was afraid I wasn't adjusting well to the realities of life. She told me "Beth, death is a fact of life. Everyone eventually dies. You're going to have to learn to deal with it." I was shocked. "You and Daddy are going to die?" I asked in utter disbelief. "...and me too?" "Well, hopefully it won't be for a long time. You don't have to go around worrying about it. When the time comes, you'll be better prepared." "No!" I cried. "It's not fair." I was devastated. This world was not the happy place I thought it was. There was no such thing as 'happily ever after'. All stories had bad endings. It was too much. This world, into which I had so recently come, was a place of nightmares. We lived in a small town. My folks knew everyone, and they were related to half of them. Someone was always dying, and it wasn't just old people. Children died. They drowned, or they played with guns and accidentally shot themselves. They even died from pneumonia or polio. Antibiotics were not widely used, and almost anything could turn deadly. Life was scary. I couldn't understand why we were here at all, if we were just going to end up dead. I tried to shut my ears to all talk of death, but it was no use. My parents talked about every little detail of how people died. The more I heard, the more traumatized I became. Mother was always trying to drag me to funerals, but I wanted no part of it. One day when I was seven, an old man who lived near us died. He was ninety-six and he'd looked like what I assumed a walking dead person might look like ever since I had known him. Now, his body was at the local funeral parlor. Mom wanted to go visit with the family. She had just picked me up from school, and she stopped the car in front of the funeral home. "Come on in with me," she told me. "It's too hot to sit out here in the car." "No! I'm not going in that place." "You won't have to see him. You can sit in the waiting room," she pleaded. "I don't want to leave you out here." "No!" I protested, with tears starting to roll down my cheeks. "O.K.," she said, finally relenting. "Let's roll the windows down, so you want get too hot. I won't be long." Mother left and went inside, and I prepared for a long wait. I knew my mother well enough to know she never hurried. I took my colors from my book bag, fished out my tablet, and started to draw a picture. After all I was going to grow up to be an artist. I had expressed an interest in art ever since age five when Mom had taken me to visit an aunt who painted. Likely because Mom gushed over her talent, I thought this might be a good career for me. I told everyone who asked that I was going to be artist when I grew up.

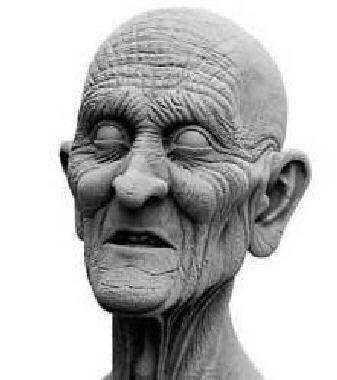

About fifteen minutes later, Mother appeared at the door of the car, holding a head. I glanced up and let out a scream which could be heard for blocks. Covering my eyes, I dived to the floorboard of the car. How could she? She was so determined to make me see a dead person, she was going to bring him out in pieces. My piercing scream startled her so bad, she almost dropped the head. Confused, she backed away and went back inside. Quickly, she returned empty-handed to find out what had so upset her sobbing daughter.

I was so hysterical it took some time to calm me down and explain what I was really seeing. The owner of the funeral parlor had a son who had recently returned home from art school. He had become quite skilled at sculpture. When Mom saw his lifelike human-size art piece, she was impressed and thought I would be interested in seeing the work of a real artist. With the permission of the funeral director, she had brought the piece out to show me. She certainly hadn't anticipated my reaction. Of course, after learning what I'd assumed was John Seay's head, she laughed until she almost wet herself. "I can't believe you actually thought I would be bringing out parts of a body for you to see. People can't do that. Do you think your mother is crazy?"

Well duh! How do I know what they do with dead bodies? I'm pretty sure you would have brought him out in out in pieces, if they would let you. I didn't say it, but I wanted too. She had been so determined to get me used to the realities of life, and she was an extremely determined woman. One thing I was sure of, this story wasn't going to be kept between the two of us. There would be plenty of laughs at my expense. In that respect, I knew my mother well.

Eventually, I outgrew my obsessive fear of death. I even learned to appreciate sculptured art pieces, but I'll never forget the sheer terror I felt when I saw my mother holding Mr. John Seay's head.

|

| ©

Copyright 2025.

BethShelby

All rights reserved. BethShelby has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work. |